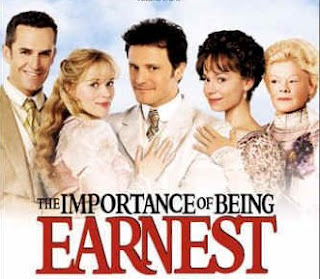

The Importance of Being Earnest

"I've now realised for the first time in my life the vital Importance of Being Earnest."

Othello

"My heart's subdued/ Even to the very quality of my lord./ I saw Othello's visage in his mind,/ And to his honors and his valiant parts/ Did I my soul and fortunes consecrate

William Shakespeare

All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players: they have their exits and their entrances; and one man in his time plays many parts, his acts being seven ages.

They flee from

They flee from me that sometime did me seek With naked foot, stalking in my chamber. I have seen them gentle, tame, and meek, That now are wild and do not remember That sometime they put themself in danger To take bread at my hand; and now they range, Busily seeking with a continual change. Thanked be fortune it hath been otherwise Twenty times better; but once in special, In thin array after a pleasant guise, When her loose gown from her shoulders did fall, And she me caught in her arms long and small; Therewithall sweetly did me kiss And softly said, “Dear heart, how like you this?” It was no dream: I lay broad waking. But all is turned thorough my gentleness Into a strange fashion of forsaking; And I have leave to go of her goodness, And she also, to use newfangleness. But since that I so kindly am served I would fain know what she hath deserved.

Doctor Faustus

The Tragicall History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus, commonly referred to simply as Doctor Faustus, is a play by Christopher Marlowe, based on the Faust story, in which a man sells his soul to the devil for power and knowledge.

pride and prejudice

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, this truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered the rightful property of some one or other of their daughters.

Poppies in October

Even the sun-clouds this morning cannot manage such skirts. Nor the woman in the ambulance Whose red heart blooms through her coat so astoundingly -- A gift, a love gift Utterly unasked for By a sky Palely and flamily Igniting its carbon monoxides, by eyes Dulled to a halt under bowlers. O my God, what am I That these late mouths should cry open In a forest of frost, in a dawn of cornflowers.

Wednesday 11 October 2017

Thursday 5 October 2017

John Keats "Ode To Autumn"

John Keats "Ode To Autumn"

The Composition of "To Autumn"

Keats wrote "To Autumn" after enjoying a lovely autumn day; he described his experience in a letter to his friend Reynolds:

"How beautiful the season is now--How fine the air. A temperate sharpness about it. Really, without joking, chaste weather--Dian skies--I never lik'd stubble fields so much as now--Aye better than the chilly green of the spring. Somehow a stubble plain looks warm--in the same way that some pictures look warm--this struck me so much in my Sunday's walk that I composed upon it."

General Comments

This ode is a favorite with critics and poetry lovers alike. Harold Bloom calls it "one of the subtlest and most beautiful of all Keats's odes, and as close to perfect as any shorter poem in the English Language." Allen Tate agrees that it "is a very nearly perfect piece of style"; however, he goes on to comment, "it has little to say."

This ode deals with the some of the concerns presented in his other odes, but there are also significant differences. (1) There is no visionary dreamer or attempted flight from reality in this poem; in fact, there is no narrative voice or persona at all. The poem is grounded in the real world; the vivid, concrete imagery immerses the reader in the sights, feel, and sounds of autumn and its progression. (2) With its depiction of the progression of autumn, the poem is an unqualified celebration of process. (I am using the words process, flux, and change interchangeably in my discussion of Keats's poems.) Keats totally accepts the natural world, with its mixture of ripening, fulfillment, dying, and death. Each stanza integrates suggestions of its opposite or its predecessors, for they are inherent in autumn also.

Because this ode describes the process of fruition and decay in autumn, keep in mind the passage of time as you read it.

Analysis

Stanza I:

Keats describes autumn with a series of specific, concrete, vivid visual images. The stanza begins with autumn at the peak of fulfillment and continues the ripening to an almost unbearable intensity. Initially autumn and the sun "load and bless" by ripening the fruit. But the apples become so numerous that their weight bends the trees; the gourds "swell," and the hazel nuts "plump." The danger of being overwhelmed by fertility that has no end is suggested in the flower and bee images in the last four lines of the stanza. Keats refers to "more" later flowers "budding" (the -ing form of the word suggests activity that is ongoing or continuing); the potentially overwhelming number of flowers is suggested by the repetition "And still more" flowers. The bees cannot handle this abundance, for their cells are "o'er-brimm'd." In other words, their cells are not just full, but are over-full or brimming over with honey.

Process or change is also suggested by the reference to Summer in line 11; the bees have been gathering and storing honey since summer. "Clammy" describes moisture; its unpleasant connotations are accepted as natural, without judgment.

Certain sounds recur in the beginning lines--s, m, l. Find the words that contain these letters; read them aloud and listen. What is the effect of these sounds--harsh, explosive, or soft? How do they contribute to the effect of the stanza, if they do?

The final point I wish to make about this stanza is subtle and sophisticated and will probably interest you only if you like grammar and enjoy studying English:

The first stanza is punctuated as one sentence, and clearly it is one unit. It is not, however, a complete sentence; it has no verb. By omitting the verb, Keats focuses on the details of ripening. In the first two and a half lines, the sun and autumn conspire (suggesting a close working relationship and intention). From lines 3 to 9, Keats constructs the details using parallelism; the details take the infinitive form (to plus a verb): "to load and bless," "To bend...and fill," "To swell...and plump," and "to set." In the last two lines, he uses a subordinate clause, also called a dependent clause (note the subordinating conjunction "until"); the subordinate or dependent clause is appropriate because the oversupply of honey is the result of--or dependent upon--the seemingly unending supply of flowers.

Stanza II

The ongoing ripening of stanza I, which if continued would become unbearable, has neared completion; this stanza slows down and contains almost no movement. Autumn, personified as a reaper or a harvester crosses a brook and watches a cider press. Otherwise, Autumn is listless and even falls asleep. Some work remains; the furrow is "half-reap'd," the winnowed hair refers to ripe grain still standing, and apple cider is still being pressed. However, the end of the cycle is near. The press is squeezing out "the last oozings." Find other words that indicate slowing down. Notice that Keats describes a reaper who is not harvesting and who is not turning the press.

Is the personification successful, that is, does nature become a person with a personality, or does nature remain an abstraction? Is there a sense of depletion, of things coming to an end? Does the slowing down of the process suggest a stopping, a dying or dead? Does the personification of autumn as a reaper with a scythe suggest another kind of reaper--the Grim Reaper?

Speak the last line of this stanza aloud, and listen to the pace (how quickly or slowly you say the words). Is Keats using the sound of words to reinforce and/or to parallel the meaning of the line?

Stanza III

Spring inline 1 has the same function as Summer in stanza I; they represent a process, the flux of time. In addition, spring is a time of a rebirth of life, an association which contrasts with the explicitly dying autumn of this stanza. Furthermore, autumn spells death for the now "full-grown" lambs which were born in spring; they are slaughtered in autumn. And the answer to the question of line 1, where is Spring's songs, is that they are past or dead. The auditory details that follow are autumn's songs.

The day, like the season, is dying. The dying of day is presented favorably, "soft-dying." Its dying also creates beauty; the setting sun casts a "bloom" of "rosy hue" over the dried stubble or stalks left after the harvest. Keats accepts all aspects of autumn; this includes the dying, and so he introduces sadness; the gnats "mourn" in a "wailful choir" and the doomed lambs bleat (Why does Keats use "lambs," rather than "sheep" here? would the words have a different effect on the reader?). It is a "light" or enjoyable wind that "lives or dies," and the treble of the robin is pleasantly "soft." The swallows are gathering for their winter migration.

Keats blends living and dying, the pleasant and the unpleasant because they are inextricably one; he accepts the reality of the mixed nature of the world.

Sunday 1 October 2017

Sylvia Plath Life and Works

Sylvia Plath Life and Works

Sylvia Plath was born on 27 October 1932, at Massachusetts Memorial Hospital, in the Jennie M Robinson Memorial maternity building in Boston, Massachusetts. Her parents were Otto Emil Plath 1885-1940) and Aurelia Schober Plath (1906-1994). She would be an only child for two and a half years when her brother Warren was born, 27 April 1935. Her first home was on 24 Prince Street in Jamaica Plain, a suburb of Boston. After Warren Plath's birth, the family moved to 92 Johnson Avenue in Winthrop, Massachusetts just east of Boston. This is where Plath became familiar and intimate with the sea. From an early age, she enjoyed the sea and could recognize its beauty & power.

Otto Plath taught at Boston University (BU). To get there, he took a bus, boat, and trolley to get to work each day from Winthrop. At that time BU's site was on Boylston Street just off Copley Square. This site is now New England Financial. Otto Plath's health began to fail shortly after the birth of his son Warren in 1935. He thought he had cancer as a friend of his, with similar symptoms, had recently lost a battle with lung cancer. Otto Plath was an expert on bees. He wrote a book called Bumblebees and Their Ways, published in 1934. Sylvia Plath was impressed with her father's handling of bees. He could catch them and they would not sting! (He caught only the males; the males do not have stingers.) Otto Plath died on 5 November 1940, only a week and a half after his daughters eighth birthday. He died of diabetes mellitus, which at the time was a very curable disease. Upon his death, a friend only asked, "How could such a brilliant man have been so stupid?"

In 1942, Aurelia Plath moved the family to 26 Elmwood Road, in Wellesley. This was Sylvia Plath's home until she began college. She repeated the fifth grade so that she would be in class with children her same age, and she aced her courses. From then on, Plath was a star student, making straight A's the whole way through high school. She excelled in English, particularly creative writing. Her first poem appeared when she was eight in the Boston Herald (10 August 1941, page B-8).

Plath won a scholarship to attend Smith College, an all-girls' school in Northampton, Massachusetts. She was ecstatic in the fall of 1950 to be a 'Smith girl.' She immediately felt the pressures of College life, from the academic rigor to the social scenes. Sylvia Plath received a scholarship to attend Smith College. The benefactress of this scholarship was Olive Higgins Prouty, a famous author. Olive Higgins Prouty lived at 393 Walnut Street in Brookline, a suburb of Boston near to Wellesley. Once at Smith, Plath started a correspondence with Olive that lasted the rest of her life. Plath wanted to be both brilliant and friendly, and she achieved both.

From around 1944 on, Plath kept a journal. The journals gained in importance to her in college. She would come to rely heavily on her journals for inspiration and documentation. She had a very quick, sharp eye, noting details that most people miss and take for granted. Her journal became her most trusted friend and confidant, telling it secrets and presenting a completely different and real self on those pages. Sometimes she was blunt, other times candid. She captured ideas for poems and stories and detailed her ambitions. One of the more memorable passages she writes about the joy of picking her nose. (January 1953)

At this point in her life, the early Smith years, she was writing very measured, pretty poems. She had the craft of poem-making down, but she did not have the voice. She was working hard on syllabics, paying close attention to line lengths, stanza lengths and a myriad of other poetic styles that any apprentice should know. Plath was different, though, as she worked herself to perfection. She relied on her thesaurus to push her way through poem after poem. She emulated Dylan Thomas, Wallace Stevens, and W.H. Auden. She read Richard Wilbur, Marianne Moore, and John Crowe Ransom. She also wanted to write short stories for women's magazines such as the Ladies Home Journal and other influential 1950s magazines. She was also sending poems and stories out regularly, facing rejection most of the time. She did, however, receive some success.

Beginning in 1950, Plath began publishing in national periodicals. Her article "Youth's Appeal for World Peace" was published in the Christian Science Monitor (CSM) on 16 March. Her short story "And Summer Will Not Come Again" appeared in the August issue of Seventeen & the poem "Bitter Strawberries" appeared in the 11 August CSM. Throughout 1951, Plath was collecting rejection slips at a fast pace, but she was also published quite a bit.

In 1953, Plath wrote articles for local newspapers like the Daily Hampshire Gazette and the Springfield Union as their Smith College correspondent. Her short story, "Sunday at the Mintons" won first prize in a Mademoiselle contest. From this story, she also won a Guest Editorship at Mademoiselle at 575 Madison Avenue in New York City during June 1953. (The offices have since moved & the magazine recently ceased publication.) She and several other young women stayed at the women-only Barbizon Hotel, at 63rd Street and Lexington Avenue. The events of this very important month are well covered in her novel, The Bell Jar. (In The Bell Jar she calls the hotel, The Amazon.) Her published journals for these months are thin and do not reveal too much about the breakdown that followed. She returned from the New York exhausted mentally, emotionally, and physically. She was banking on being admitted to a Harvard summer class on writing. When she received word she had not been accepted, Sylvia Plath's fate was also secured. Her journals end abruptly in July. For details of the summer of 1953, readers must rely on information Plath put down in a few letters to friends and in her novel, The Bell Jar.

Throughout July and early August, Plath tells us in The Bell Jar that she could neither read nor sleep nor write. In an interview given to the Voices & Visions audio/video series, Aurelia Plath tells us that her daughter could in fact read and that she meticulously read Freud's Abnormal Psychology. Plath, however, felt despondent. On 24 August 1953, she left a note saying, "Have gone for a long walk. Will be home tomorrow." She took a blanket, a bottle of sleeping pills, a glass of water with her down the stairs to the cellar. There she crept into a two and a half-foot entrance to the crawl space underneath the screened-in porch. She began swallowing the pills in gulps of water and fell unconscious.

Aurelia Plath gave a good fight into finding her missing daughter, barely waiting a few hours to phone the police. An exhaustive search started in the Great Boston area to try and find the missing Smith beauty. Boy scouts and local police and neighbors combed Wellesley thoroughly through small parks as well as in and around Morse's Pond. Headlines in the papers the next day, 25 August 1953, alerted many of Plath's friends. Headlines were less favorable the next day, Wednesday 26 August 1953. However, around lunchtime, Plath was found with eight sleeping pills still in the bottle. Sylvia was treated at McLean Hospital in Belmont with the help of her Smith benefactress Olive Higgins Prouty. Her doctor was Ruth Barnhouse Beuscher, and Dr. Beuscher would go on to be a great help to Plath in the years to come. Her recovery was not easy, but Plath pulled through and was readmitted to Smith for the spring 1954 semester. This is really the beginning of Sylvia Plath, poet.

1954 was a remarkable year. She met Richard Sassoon, who would later play a significant role as lover. Plath also continued where she left off at Smith, doing excellent work in spite of the breakdown. That summer she studied at Harvard Summer School, living with Nancy Hunter-Steiner in apartment 4 at the Bay State Apartments, located at 1572 Massachusetts Avenue.

The next school year at Smith, Plath worked hard, continuing her excellence. In the spring 1955 semester, Plath turned in her English honors thesis, The Magic Mirror: The Double in Dostoevsky. She graduated summa cum laude and also won a Fulbright Scholarship to study at Newnham College, Cambridge University.

Before Plath left for England, however, she needed to get through a summer of living at 26 Elmwood Road where her first suicide attempt, two years earlier, occurred. She spent much of her time dating young men like Richard Sassoon, Gordon Lameyer and toward the end of the summer, an editor named Peter Davison. However, before setting sail, Plath ended these attachments, preferring to take on what England had to offer. As Plath sailed to England, she spent her time "flirting and then making love" (Wagner-Martin). Plath was excited about Cambridge for many reasons, two of which were its possible for the best education and to find a man to marry (at that time men outnumbered women at Cambridge by the astonishing ten to one).

As an American in England, Plath was shocked and overwhelmed by Cambridge. Coming to England in mid-September, Plath spent her first ten days in London, sightseeing, and shopping. When she arrived at 4 Barton Road and Whitstead she was at first disappointed as it is at the back of the college. She loved Cambridge though and immediately became familiar with its old streets and customs. British schooling is very different than in America so Plath had major adjustments ahead of her. She had to choose her courses for two years and at the end of the second year were the exams. This meant many studies on her own, though she was responsible for writing essays weekly on topics, attending lectures and meeting one hour a week with her tutors. Plath's tutor, Dorothea Krook, would become a very important female role model in the coming years, much as Dr. Ruth Beuscher was to her. Krook taught Plath in a course on Henry James and the Moralists. Her academic course load was much lighter than it was at Smith, so that autumn Plath joined the Amateur Dramatics Club (ADC) and had a small role as an insane poetess. Initially, she tried to steer clear of dating as she grew accustomed to life in a foreign country. She still maintained relations with Richard Sassoon, who was living in Paris at the time. Plath spent her winter holiday with Sassoon in and around Paris and Europe. However romantic this holiday was, Sassoon soon wrote to Plath asking for a break, telling Plath that he would contact her when he was ready.

Plath, back at Cambridge and not too happy with the English winter, began falling ill and sinking into a depression. She suffered from a splinter in her eye which became the subject of the poem "The Eye-Mote", and along with a cold & flu, began to think she would not conquer Cambridge after all. On 25 February Plath met with a psychiatrist named Dr. Davy and in her journal entry for that day-expressed anger at Sassoon. At the ripe age of 23, Plath really needed someone to love and to love her. To be 23 and single in 1953 was considered to be passed her prime.

That afternoon after the meeting with Dr. Davy, Plath bought a copy of the Saint Botolph's Review and read impressive poems by E Lucas Myers and more impressive poems by a poet called Ted Hughes. Plath was told of a party that evening celebrating the publication of this new literary review to be held at Falcon Yard.

The meeting of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes is probably the best-known meeting of two aspiring poets in the 20th century. Plath walked into the room with a date named Hamish and quickly began enquiring as to Hughes' whereabouts. She found him, recited some of his poems, which in the few hours since first reading they had memorized. According to her journals and letters, they were dancing and stamping and yelling and drinking and then he kissed her on the neck and she bit Hughes on the cheek, and he bled. No matter what sort of hyperbole was used in the retelling of their meeting, it was dramatic and life-changing. Hughes' voice boomed like the thunder of God, and his Yorkshire accent was deep and intense. She wrote the poem "Pursuit" to him and in the poem, she calls him a panther. It is also in this poem that Plath announces with some clairvoyance that "One day I'll have my death of him." Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes both found influences in W.B Yeats, Dylan Thomas, and D. H. Lawrence, to name a few. Hughes read these poets as well and also Hopkins, Blake, Chaucer, and Shakespeare. There is no doubt that Hughes helped Plath achieve the major poetic voice she would later find. The voice might have always been in Plath, the talent and drive were certainly there.

That spring Plath suffered much heartache and confusion over her love for Richard Sassoon, who had asked Plath not to contact him until he figured out what he wanted (he was in love with at least two other women). Plath traveled to London for one night before going to Paris for her spring break and she stayed with Ted Hughes at his flat at 18 Rugby Street. They made hectic love all night long and then she traveled to Paris in search of Sassoon to find some resolution. Sassoon's decision could not have been any clearer; he was far away from Paris and did not want to be found. Plath, finding her letters unanswered at Sassoon's residence, became desperate, frequenting places she and Sassoon previously visited. Plath met several other friends from Cambridge, some strangers and finally had a bad time of traveling through Italy with her ex-flame Gordon Lameyer. Plath received at least one love letter from Hughes, which lifted her. She flew from Rome to London to be with Hughes, leaving Lameyer behind.

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes married on Bloomsday 1956 (16 June) at the Church of St. George-the-Martyr at Queen's Square, Bloomsbury, just a few paces from the offices of Faber & Faber. Aurelia Plath was there to witness. The Hughes spent the summer writing and no doubt getting to know each other better in Benidorm, Spain. The couple also spent in Paris, France, and Alicante, Spain, before visiting Yorkshire, to be with Ted's parents, who knew nothing of the wedding.

In the fall, Plath continued studying at Cambridge. Eventually, Plath moved into a flat located at 55 Eltisley Avenue with Ted Hughes. Ironically, some relatives of Richard Sassoon lived above them. The two poets would study, cook, eat, take walks and learn to live with each other. Ted Hughes took a job teaching at a local boy's school. This would be one of his most enjoyable jobs. Plath and Hughes made arrangements to go to America in the summer of 1957.

Immediately upon their meeting, Plath began typing and sending out Hughes's poems publishers in America and England. Due in part to this work, in early 1957, Ted Hughes won first prize in the New York Poetry Center contests judged by Marianne Moore, W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender for his book The Hawk in the Rain. This was a contest he was unaware he entered. His publishers would be Harper & Row and they would bring the book out that summer. Plath had been writing some very good poems this English winter, among them "Sow," "The Thin People," and "Hardcastle Crags." On 12 March 1957 Plath was offered a teaching position in Freshman English at Smith College.

Friday 29 September 2017

Thursday 28 September 2017

THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS - XII. THE RETURN OF ULYSSES

THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS

By Kenneth Grahame

Author Of “The Golden Age,” “Dream Days,” Etc.

XII. THE RETURN OF ULYSSES

When it began to grow dark, the Rat, with an air of excitement and

mystery, summoned them back into the parlour, stood each of them up

alongside of his little heap, and proceeded to dress them up for the

coming expedition. He was very earnest and thoroughgoing about it, and

the affair took quite a long time. First, there was a belt to go round

each animal, and then a sword to be stuck into each belt, and then

a cutlass on the other side to balance it. Then a pair of pistols, a

policeman’s truncheon, several sets of handcuffs, some bandages and

sticking-plaster, and a flask and a sandwich-case. The Badger laughed

good-humouredly and said, ‘All right, Ratty! It amuses you and it

doesn’t hurt me. I’m going to do all I’ve got to do with this here

stick.’ But the Rat only said, ‘PLEASE, Badger. You know I shouldn’t

like you to blame me afterwards and say I had forgotten ANYTHING!’

When all was quite ready, the Badger took a dark lantern in one paw,

grasped his great stick with the other, and said, ‘Now then, follow me!

Mole first, ‘cos I’m very pleased with him; Rat next; Toad last. And

look here, Toady! Don’t you chatter so much as usual, or you’ll be sent

back, as sure as fate!’

The Toad was so anxious not to be left out that he took up the inferior

position assigned to him without a murmur, and the animals set off. The

Badger led them along by the river for a little way, and then suddenly

swung himself over the edge into a hole in the river-bank, a little

above the water. The Mole and the Rat followed silently, swinging

themselves successfully into the hole as they had seen the Badger do;

but when it came to Toad’s turn, of course he managed to slip and fall

into the water with a loud splash and a squeal of alarm. He was hauled

out by his friends, rubbed down and wrung out hastily, comforted, and

set on his legs; but the Badger was seriously angry, and told him that

the very next time he made a fool of himself he would most certainly be

left behind.

So at last they were in the secret passage, and the cutting-out

expedition had really begun!

It was cold, and dark, and damp, and low, and narrow, and poor Toad

began to shiver, partly from dread of what might be before him, partly

because he was wet through. The lantern was far ahead, and he could not

help lagging behind a little in the darkness. Then he heard the Rat call

out warningly, ‘COME on, Toad!’ and a terror seized him of being left

behind, alone in the darkness, and he ‘came on’ with such a rush that

he upset the Rat into the Mole and the Mole into the Badger, and for a

moment all was confusion. The Badger thought they were being attacked

from behind, and, as there was no room to use a stick or a cutlass, drew

a pistol, and was on the point of putting a bullet into Toad. When he

found out what had really happened he was very angry indeed, and said,

‘Now this time that tiresome Toad SHALL be left behind!’

But Toad whimpered, and the other two promised that they would be

answerable for his good conduct, and at last the Badger was pacified,

and the procession moved on; only this time the Rat brought up the rear,

with a firm grip on the shoulder of Toad.

So they groped and shuffled along, with their ears pricked up and their

paws on their pistols, till at last the Badger said, ‘We ought by now to

be pretty nearly under the Hall.’

Then suddenly they heard, far away as it might be, and yet apparently

nearly over their heads, a confused murmur of sound, as if people were

shouting and cheering and stamping on the floor and hammering on tables.

The Toad’s nervous terrors all returned, but the Badger only remarked

placidly, ‘They ARE going it, the Weasels!’

The passage now began to slope upwards; they groped onward a little

further, and then the noise broke out again, quite distinct this time,

and very close above them. ‘Ooo-ray-ooray-oo-ray-ooray!’ they heard, and

the stamping of little feet on the floor, and the clinking of glasses

as little fists pounded on the table. ‘WHAT a time they’re having!’ said

the Badger. ‘Come on!’ They hurried along the passage till it came to a

full stop, and they found themselves standing under the trap-door that

led up into the butler’s pantry.

Such a tremendous noise was going on in the banqueting-hall that there

was little danger of their being overheard. The Badger said, ‘Now, boys,

all together!’ and the four of them put their shoulders to the trap-door

and heaved it back. Hoisting each other up, they found themselves

standing in the pantry, with only a door between them and the

banqueting-hall, where their unconscious enemies were carousing.

The noise, as they emerged from the passage, was simply deafening. At

last, as the cheering and hammering slowly subsided, a voice could

be made out saying, ‘Well, I do not propose to detain you much

longer’--(great applause)--‘but before I resume my seat’--(renewed

cheering)--‘I should like to say one word about our kind host, Mr. Toad.

We all know Toad!’--(great laughter)--‘GOOD Toad, MODEST Toad, HONEST

Toad!’ (shrieks of merriment).

‘Only just let me get at him!’ muttered Toad, grinding his teeth.

‘Hold hard a minute!’ said the Badger, restraining him with difficulty.

‘Get ready, all of you!’

‘--Let me sing you a little song,’ went on the voice, ‘which I have

composed on the subject of Toad’--(prolonged applause).

Then the Chief Weasel--for it was he--began in a high, squeaky voice--

‘Toad he went a-pleasuring

Gaily down the street--’

The Badger drew himself up, took a firm grip of his stick with both

paws, glanced round at his comrades, and cried--

‘The hour is come! Follow me!’

And flung the door open wide.

My!

What a squealing and a squeaking and a screeching filled the air!

Well might the terrified weasels dive under the tables and spring madly

up at the windows! Well might the ferrets rush wildly for the fireplace

and get hopelessly jammed in the chimney! Well might tables and chairs

be upset, and glass and china be sent crashing on the floor, in the

panic of that terrible moment when the four Heroes strode wrathfully

into the room! The mighty Badger, his whiskers bristling, his great

cudgel whistling through the air; Mole, black and grim, brandishing his

stick and shouting his awful war-cry, ‘A Mole! A Mole!’ Rat; desperate

and determined, his belt bulging with weapons of every age and every

variety; Toad, frenzied with excitement and injured pride, swollen to

twice his ordinary size, leaping into the air and emitting Toad-whoops

that chilled them to the marrow! ‘Toad he went a-pleasuring!’ he yelled.

‘I’LL pleasure ‘em!’ and he went straight for the Chief Weasel. They

were but four in all, but to the panic-stricken weasels the hall seemed

full of monstrous animals, grey, black, brown and yellow, whooping and

flourishing enormous cudgels; and they broke and fled with squeals

of terror and dismay, this way and that, through the windows, up the

chimney, anywhere to get out of reach of those terrible sticks.

The affair was soon over. Up and down, the whole length of the hall,

strode the four Friends, whacking with their sticks at every head that

showed itself; and in five minutes the room was cleared. Through the

broken windows the shrieks of terrified weasels escaping across the lawn

were borne faintly to their ears; on the floor lay prostrate some dozen

or so of the enemy, on whom the Mole was busily engaged in fitting

handcuffs. The Badger, resting from his labours, leant on his stick and

wiped his honest brow.

‘Mole,’ he said,’ ‘you’re the best of fellows! Just cut along outside

and look after those stoat-sentries of yours, and see what they’re

doing. I’ve an idea that, thanks to you, we shan’t have much trouble

from them to-night!’

The Mole vanished promptly through a window; and the Badger bade the

other two set a table on its legs again, pick up knives and forks and

plates and glasses from the debris on the floor, and see if they could

find materials for a supper. ‘I want some grub, I do,’ he said, in that

rather common way he had of speaking. ‘Stir your stumps, Toad, and look

lively! We’ve got your house back for you, and you don’t offer us so

much as a sandwich.’ Toad felt rather hurt that the Badger didn’t say

pleasant things to him, as he had to the Mole, and tell him what a

fine fellow he was, and how splendidly he had fought; for he was rather

particularly pleased with himself and the way he had gone for the Chief

Weasel and sent him flying across the table with one blow of his stick.

But he bustled about, and so did the Rat, and soon they found some guava

jelly in a glass dish, and a cold chicken, a tongue that had hardly

been touched, some trifle, and quite a lot of lobster salad; and in the

pantry they came upon a basketful of French rolls and any quantity of

cheese, butter, and celery. They were just about to sit down when the

Mole clambered in through the window, chuckling, with an armful of

rifles.

‘It’s all over,’ he reported. ‘From what I can make out, as soon as the

stoats, who were very nervous and jumpy already, heard the shrieks and

the yells and the uproar inside the hall, some of them threw down their

rifles and fled. The others stood fast for a bit, but when the weasels

came rushing out upon them they thought they were betrayed; and the

stoats grappled with the weasels, and the weasels fought to get away,

and they wrestled and wriggled and punched each other, and rolled

over and over, till most of ‘em rolled into the river! They’ve all

disappeared by now, one way or another; and I’ve got their rifles. So

that’s all right!’

‘Excellent and deserving animal!’ said the Badger, his mouth full of

chicken and trifle. ‘Now, there’s just one more thing I want you to do,

Mole, before you sit down to your supper along of us; and I wouldn’t

trouble you only I know I can trust you to see a thing done, and I wish

I could say the same of every one I know. I’d send Rat, if he wasn’t a

poet. I want you to take those fellows on the floor there upstairs with

you, and have some bedrooms cleaned out and tidied up and made really

comfortable. See that they sweep UNDER the beds, and put clean sheets

and pillow-cases on, and turn down one corner of the bed-clothes, just

as you know it ought to be done; and have a can of hot water, and clean

towels, and fresh cakes of soap, put in each room. And then you can give

them a licking a-piece, if it’s any satisfaction to you, and put them

out by the back-door, and we shan’t see any more of THEM, I fancy. And

then come along and have some of this cold tongue. It’s first rate. I’m

very pleased with you, Mole!’

The goodnatured Mole picked up a stick, formed his prisoners up in a

line on the floor, gave them the order ‘Quick march!’ and led his squad

off to the upper floor. After a time, he appeared again, smiling, and

said that every room was ready, and as clean as a new pin. ‘And I didn’t

have to lick them, either,’ he added. ‘I thought, on the whole, they had

had licking enough for one night, and the weasels, when I put the point

to them, quite agreed with me, and said they wouldn’t think of troubling

me. They were very penitent, and said they were extremely sorry for

what they had done, but it was all the fault of the Chief Weasel and the

stoats, and if ever they could do anything for us at any time to make

up, we had only got to mention it. So I gave them a roll a-piece, and

let them out at the back, and off they ran, as hard as they could!’

Then the Mole pulled his chair up to the table, and pitched into the

cold tongue; and Toad, like the gentleman he was, put all his jealousy

from him, and said heartily, ‘Thank you kindly, dear Mole, for all

your pains and trouble tonight, and especially for your cleverness this

morning!’ The Badger was pleased at that, and said, ‘There spoke my

brave Toad!’ So they finished their supper in great joy and contentment,

and presently retired to rest between clean sheets, safe in Toad’s

ancestral home, won back by matchless valour, consummate strategy, and a

proper handling of sticks.

The following morning, Toad, who had overslept himself as usual, came

down to breakfast disgracefully late, and found on the table a certain

quantity of egg-shells, some fragments of cold and leathery toast, a

coffee-pot three-fourths empty, and really very little else; which did

not tend to improve his temper, considering that, after all, it was his

own house. Through the French windows of the breakfast-room he could

see the Mole and the Water Rat sitting in wicker-chairs out on the lawn,

evidently telling each other stories; roaring with laughter and kicking

their short legs up in the air. The Badger, who was in an arm-chair and

deep in the morning paper, merely looked up and nodded when Toad entered

the room. But Toad knew his man, so he sat down and made the best

breakfast he could, merely observing to himself that he would get square

with the others sooner or later. When he had nearly finished, the Badger

looked up and remarked rather shortly: ‘I’m sorry, Toad, but I’m afraid

there’s a heavy morning’s work in front of you. You see, we really ought

to have a Banquet at once, to celebrate this affair. It’s expected of

you--in fact, it’s the rule.’

‘O, all right!’ said the Toad, readily. ‘Anything to oblige. Though

why on earth you should want to have a Banquet in the morning I cannot

understand. But you know I do not live to please myself, but merely to

find out what my friends want, and then try and arrange it for ‘em, you

dear old Badger!’

‘Don’t pretend to be stupider than you really are,’ replied the Badger,

crossly; ‘and don’t chuckle and splutter in your coffee while you’re

talking; it’s not manners. What I mean is, the Banquet will be at night,

of course, but the invitations will have to be written and got off at

once, and you’ve got to write ‘em. Now, sit down at that table--there’s

stacks of letter-paper on it, with “Toad Hall” at the top in blue and

gold--and write invitations to all our friends, and if you stick to it

we shall get them out before luncheon. And I’LL bear a hand, too; and

take my share of the burden. I’LL order the Banquet.’

‘What!’ cried Toad, dismayed. ‘Me stop indoors and write a lot of

rotten letters on a jolly morning like this, when I want to go around my

property, and set everything and everybody to rights, and swagger about

and enjoy myself! Certainly not! I’ll be--I’ll see you----Stop a minute,

though! Why, of course, dear Badger! What is my pleasure or convenience

compared with that of others! You wish it done, and it shall be done.

Go, Badger, order the Banquet, order what you like; then join our young

friends outside in their innocent mirth, oblivious of me and my cares

and toils. I sacrifice this fair morning on the altar of duty and

friendship!’

The Badger looked at him very suspiciously, but Toad’s frank, open

countenance made it difficult to suggest any unworthy motive in this

change of attitude. He quitted the room, accordingly, in the direction

of the kitchen, and as soon as the door had closed behind him, Toad

hurried to the writing-table. A fine idea had occurred to him while he

was talking. He WOULD write the invitations; and he would take care to

mention the leading part he had taken in the fight, and how he had laid

the Chief Weasel flat; and he would hint at his adventures, and what a

career of triumph he had to tell about; and on the fly-leaf he would set

out a sort of a programme of entertainment for the evening--something

like this, as he sketched it out in his head:--

SPEECH. . . . BY TOAD.

(There will be other speeches by TOAD during the evening.)

ADDRESS. . . BY TOAD

SYNOPSIS--Our Prison System--the Waterways of Old

England--Horse-dealing, and how to deal--Property,

its rights and its duties--Back to the Land--

A Typical English Squire.

SONG. . . . BY TOAD. (Composed by himself.)

OTHER COMPOSITIONS. BY TOAD

will be sung in the course of the evening

by the. . . COMPOSER.

The idea pleased him mightily, and he worked very hard and got all the

letters finished by noon, at which hour it was reported to him that

there was a small and rather bedraggled weasel at the door, inquiring

timidly whether he could be of any service to the gentlemen. Toad

swaggered out and found it was one of the prisoners of the previous

evening, very respectful and anxious to please. He patted him on the

head, shoved the bundle of invitations into his paw, and told him to

cut along quick and deliver them as fast as he could, and if he liked

to come back again in the evening, perhaps there might be a shilling

for him, or, again, perhaps there mightn’t; and the poor weasel seemed

really quite grateful, and hurried off eagerly to do his mission.

When the other animals came back to luncheon, very boisterous and

breezy after a morning on the river, the Mole, whose conscience had been

pricking him, looked doubtfully at Toad, expecting to find him sulky or

depressed. Instead, he was so uppish and inflated that the Mole began

to suspect something; while the Rat and the Badger exchanged significant

glances.

As soon as the meal was over, Toad thrust his paws deep into his

trouser-pockets, remarked casually, ‘Well, look after yourselves, you

fellows! Ask for anything you want!’ and was swaggering off in the

direction of the garden, where he wanted to think out an idea or two for

his coming speeches, when the Rat caught him by the arm.

Toad rather suspected what he was after, and did his best to get away;

but when the Badger took him firmly by the other arm he began to see

that the game was up. The two animals conducted him between them into

the small smoking-room that opened out of the entrance-hall, shut the

door, and put him into a chair. Then they both stood in front of

him, while Toad sat silent and regarded them with much suspicion and

ill-humour.

‘Now, look here, Toad,’ said the Rat. ‘It’s about this Banquet, and

very sorry I am to have to speak to you like this. But we want you to

understand clearly, once and for all, that there are going to be no

speeches and no songs. Try and grasp the fact that on this occasion

we’re not arguing with you; we’re just telling you.’

Toad saw that he was trapped. They understood him, they saw through him,

they had got ahead of him. His pleasant dream was shattered.

‘Mayn’t I sing them just one LITTLE song?’ he pleaded piteously.

‘No, not ONE little song,’ replied the Rat firmly, though his heart bled

as he noticed the trembling lip of the poor disappointed Toad. ‘It’s no

good, Toady; you know well that your songs are all conceit and boasting

and vanity; and your speeches are all self-praise and--and--well, and

gross exaggeration and--and----’

‘And gas,’ put in the Badger, in his common way.

‘It’s for your own good, Toady,’ went on the Rat. ‘You know you MUST

turn over a new leaf sooner or later, and now seems a splendid time to

begin; a sort of turning-point in your career. Please don’t think that

saying all this doesn’t hurt me more than it hurts you.’

Toad remained a long while plunged in thought. At last he raised his

head, and the traces of strong emotion were visible on his features.

‘You have conquered, my friends,’ he said in broken accents. ‘It was,

to be sure, but a small thing that I asked--merely leave to blossom

and expand for yet one more evening, to let myself go and hear the

tumultuous applause that always seems to me--somehow--to bring out my

best qualities. However, you are right, I know, and I am wrong. Hence

forth I will be a very different Toad. My friends, you shall never have

occasion to blush for me again. But, O dear, O dear, this is a hard

world!’

And, pressing his handkerchief to his face, he left the room, with

faltering footsteps.

‘Badger,’ said the Rat, ‘_I_ feel like a brute; I wonder what YOU feel

like?’

‘O, I know, I know,’ said the Badger gloomily. ‘But the thing had to be

done. This good fellow has got to live here, and hold his own, and be

respected. Would you have him a common laughing-stock, mocked and jeered

at by stoats and weasels?’

‘Of course not,’ said the Rat. ‘And, talking of weasels, it’s lucky we

came upon that little weasel, just as he was setting out with Toad’s

invitations. I suspected something from what you told me, and had a look

at one or two; they were simply disgraceful. I confiscated the lot,

and the good Mole is now sitting in the blue boudoir, filling up plain,

simple invitation cards.’

* * * * *

At last the hour for the banquet began to draw near, and Toad, who on

leaving the others had retired to his bedroom, was still sitting there,

melancholy and thoughtful. His brow resting on his paw, he pondered long

and deeply. Gradually his countenance cleared, and he began to smile

long, slow smiles. Then he took to giggling in a shy, self-conscious

manner. At last he got up, locked the door, drew the curtains across

the windows, collected all the chairs in the room and arranged them in a

semicircle, and took up his position in front of them, swelling visibly.

Then he bowed, coughed twice, and, letting himself go, with uplifted

voice he sang, to the enraptured audience that his imagination so

clearly saw.

TOAD’S LAST LITTLE SONG!

The Toad--came--home!

There was panic in the parlours and howling in the halls,

There was crying in the cow-sheds and shrieking in the stalls,

When the Toad--came--home!

When the Toad--came--home!

There was smashing in of window and crashing in of door,

There was chivvying of weasels that fainted on the floor,

When the Toad--came--home!

Bang! go the drums!

The trumpeters are tooting and the soldiers are saluting,

And the cannon they are shooting and the motor-cars are hooting,

As the--Hero--comes!

Shout--Hoo-ray!

And let each one of the crowd try and shout it very loud,

In honour of an animal of whom you’re justly proud,

For it’s Toad’s--great--day!

He sang this very loud, with great unction and expression; and when he

had done, he sang it all over again.

Then he heaved a deep sigh; a long, long, long sigh.

Then he dipped his hairbrush in the water-jug, parted his hair in the

middle, and plastered it down very straight and sleek on each side of

his face; and, unlocking the door, went quietly down the stairs to greet

his guests, who he knew must be assembling in the drawing-room.

All the animals cheered when he entered, and crowded round to

congratulate him and say nice things about his courage, and his

cleverness, and his fighting qualities; but Toad only smiled faintly,

and murmured, ‘Not at all!’ Or, sometimes, for a change, ‘On the

contrary!’ Otter, who was standing on the hearthrug, describing to an

admiring circle of friends exactly how he would have managed things had

he been there, came forward with a shout, threw his arm round Toad’s

neck, and tried to take him round the room in triumphal progress; but

Toad, in a mild way, was rather snubby to him, remarking gently, as he

disengaged himself, ‘Badger’s was the mastermind; the Mole and the Water

Rat bore the brunt of the fighting; I merely served in the ranks and did

little or nothing.’ The animals were evidently puzzled and taken aback

by this unexpected attitude of his; and Toad felt, as he moved from one

guest to the other, making his modest responses, that he was an object

of absorbing interest to every one.

The Badger had ordered everything of the best, and the banquet was a

great success. There was much talking and laughter and chaff among the

animals, but through it all Toad, who of course was in the chair, looked

down his nose and murmured pleasant nothings to the animals on either

side of him. At intervals he stole a glance at the Badger and the Rat,

and always when he looked they were staring at each other with their

mouths open; and this gave him the greatest satisfaction. Some of the

younger and livelier animals, as the evening wore on, got whispering

to each other that things were not so amusing as they used to be in the

good old days; and there were some knockings on the table and cries of

‘Toad! Speech! Speech from Toad! Song! Mr. Toad’s song!’ But Toad only

shook his head gently, raised one paw in mild protest, and, by pressing

delicacies on his guests, by topical small-talk, and by earnest

inquiries after members of their families not yet old enough to appear

at social functions, managed to convey to them that this dinner was

being run on strictly conventional lines.

He was indeed an altered Toad!

* * * * *

After this climax, the four animals continued to lead their lives,

so rudely broken in upon by civil war, in great joy and contentment,

undisturbed by further risings or invasions. Toad, after due

consultation with his friends, selected a handsome gold chain and locket

set with pearls, which he dispatched to the gaoler’s daughter with

a letter that even the Badger admitted to be modest, grateful, and

appreciative; and the engine-driver, in his turn, was properly thanked

and compensated for all his pains and trouble. Under severe compulsion

from the Badger, even the barge-woman was, with some trouble, sought

out and the value of her horse discreetly made good to her; though Toad

kicked terribly at this, holding himself to be an instrument of Fate,

sent to punish fat women with mottled arms who couldn’t tell a real

gentleman when they saw one. The amount involved, it was true, was not

very burdensome, the gipsy’s valuation being admitted by local assessors

to be approximately correct.

Sometimes, in the course of long summer evenings, the friends would take

a stroll together in the Wild Wood, now successfully tamed so far as

they were concerned; and it was pleasing to see how respectfully they

were greeted by the inhabitants, and how the mother-weasels would bring

their young ones to the mouths of their holes, and say, pointing, ‘Look,

baby! There goes the great Mr. Toad! And that’s the gallant Water Rat, a

terrible fighter, walking along o’ him! And yonder comes the famous Mr.

Mole, of whom you so often have heard your father tell!’ But when their

infants were fractious and quite beyond control, they would quiet them

by telling how, if they didn’t hush them and not fret them, the terrible

grey Badger would up and get them. This was a base libel on Badger, who,

though he cared little about Society, was rather fond of children; but

it never failed to have its full effect.

End of Project Gutenberg’s The Wind in the Willows, by Kenneth Grahame

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS ***

THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS- XI. ‘LIKE SUMMER TEMPESTS CAME HIS TEARS’

THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS

By Kenneth Grahame

Author Of “The Golden Age,” “Dream Days,” Etc.